A Problem About Stacking Boxes

This post is about the solution to a algorithm puzzle involving stacking boxes. This is an original problem proposed by me which appeared in the CMI Online Programming Contest, 2013, hosted on HackerRank. Even though I came up with this problem independently, given that it has an intuitive formulation and an easy solution I wouldn’t be surprised if it appeared somewhere else before.

For the complete problem statement including a motivating story, constraints on parameters and example instances please check out the problem titled ‘Boxes’ in the complete list of problems.

Problem Statement

The problem statement can be summarized as follows:

We are given $N$ rectangles with integer widths and heights $(W_1, H_1), (W_2, H_2) \cdots , (W_N, H_N)$. Box $i$ can be stacked on top of box $j$ if $W_i < W_j$. However, it is also possible to ‘rotate’ either box by swapping the tuple $ (W_i, H_i)$. What is the most number of boxes that can be stacked on top of each other?

Formally, in order to stack box $i$ on top of box $j$, we need $ X_i < X_j $ where $ X_i \in \{W_i, H_i\} $ and $ X_j \in \{W_j, H_j\} $. We want to find the longest sequence $ \{ i_1, i_2, \ldots , i_k\}$ where each $ i_r \in [N] $ such for each $ i_r $, we have a fixed $ X_{i_r} \in \{ W_{i_r}, H_{i_r} \} $.

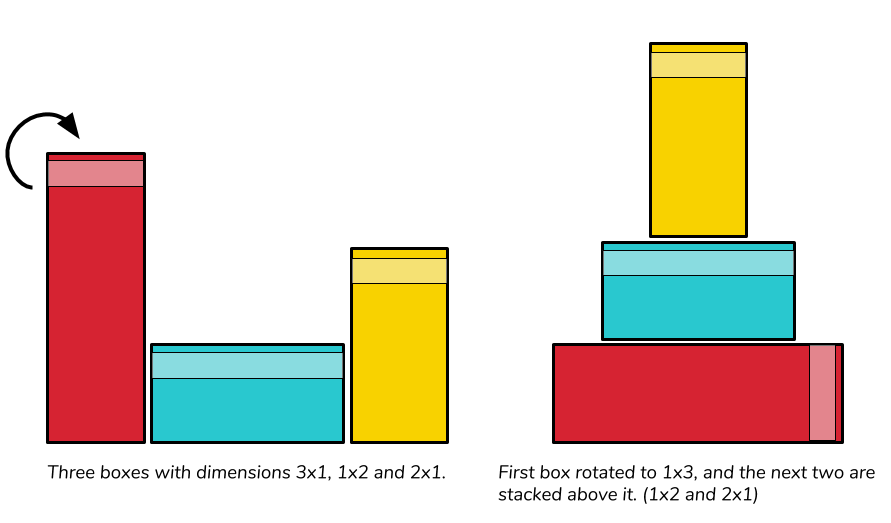

Here is one problem instance illustrated. Given rectangles $ 1 \times 3, 2 \times 1 $ and $ 1 \times 2 $, we can rotate the first rectangle and create the stack $ 1 \times 2 \prec 2 \times 1 \prec 3 \times 1 $.

Some Greedy Strategies that Don’t Work

Here are some natural greedy algorithms which would yield suboptimal solutions. These are helpful in understanding some of the nuances of the problem.

Greedy Strategy 1: Choose the box with the largest width (or height) and place it at the bottom. Break ties arbitrarily. And continue picking the next largest box that can be placed on top of the current stack finally discarding any boxes that didn’t get picked.

Greedy Strategy 2 : Choose the box with the largest width (or height) but break ties such that the box with the smaller other dimension gets selected.

Coming up with counterexamples to strategies 1 and 2 are left as exercises to the reader. :)

First Steps: What if Rotation Wasn’t Allowed

To make some initial progress, let’s tackle a much simpler version of the problem. Imagine that rotation is not allowed for the boxes. Now, we just have to choose the sequence of boxes so that the following inequality holds: $ W_{i_1} < W_{i_2} < \cdots W_{i_k} $. The answer in this case is obvious: it’s the number of distinct widths among $ N $ boxes.

Armed with this simple observation, we can rephrase the original problem. For each box $(W, H)$, we have to select either the width $(W)$ or the height $ (H) $, so that the number of distinct numbers is maximized.

From this formulation, we can immediately make some progress. If either $W$ or $H$ does not appear as a dimension for another box, (say, $H$) then we can select $H$, add this to our final count, and forget about this box. Thus, we can assume that now we only have boxes where both $W$ and $H$ appear as widths or heights of other boxes.

It becomes clear where the difficulty lies, making a choice ($W$ or $H$) means that choosing the same number for another box wouldn’t make sense. Hence, somehow we have to quantify which one of $W$ or $H$ is less ‘supported’ by other boxes.

A Graphical Representation

Now that we have some structure in our problem, it may be helpful to use the language of graph theory.

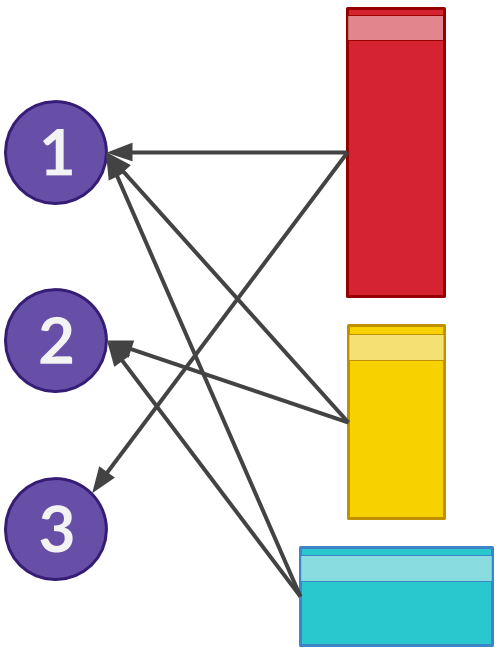

Consider a bipartite graph, where the numbers are on the left hand side and boxes are on the right hand side. Each box $(W, H)$ on the RHS has exactly two edges, one to Node $W$ and another to Node $H$.

In case $W = H$, we can just delete the box, remove the node $W (=H)$ from the graph and add +1 to our objective. Also, if a number $X$ has only one edge corresponding to a single box, say $(X, Y)$ then we can also take this box in our solution and delete the box and the number from the graph. Thus, we can assume that every number on the left side has degree at least 2.

Assumption 1: Every node (number) on the LHS has degree at least 2. Every node (box) on the RHS has degree exactly 2.

The task now becomes a classical problem, finding a maximum matching in a bipartite graph. This graph, however, has special structure which makes finding one easier and faster than the general case.

No Numbers Left Behind

Now we show that, surprisingly, all remaining numbers can be successfully matched with a box. If you saw this coming: kudos! If not, I’d suggest trying to prove this yourself before reading ahead. :)

This can be solved very quickly using Hall’s Marriage Theorem. This is a neat theorem which says that you can find a matching saturating the LHS if every subset $S$ on the LHS is incident on at least $|S|$ nodes on the RHS.

The application is as follows. Consider any subset $S$ of the number on the LHS, then the number of edges emanating from it must be at least $2|S|$, using Assumption 1. Since every node on the RHS has degree exactly $2$, it must be incident on at least $(2|S|)/2 = |S|$ node on the RHS.

We can also prove this without invoking Hall’s Marriage Theorem. We prove by contradiction that a maximum matching must include all nodes on the LHS.

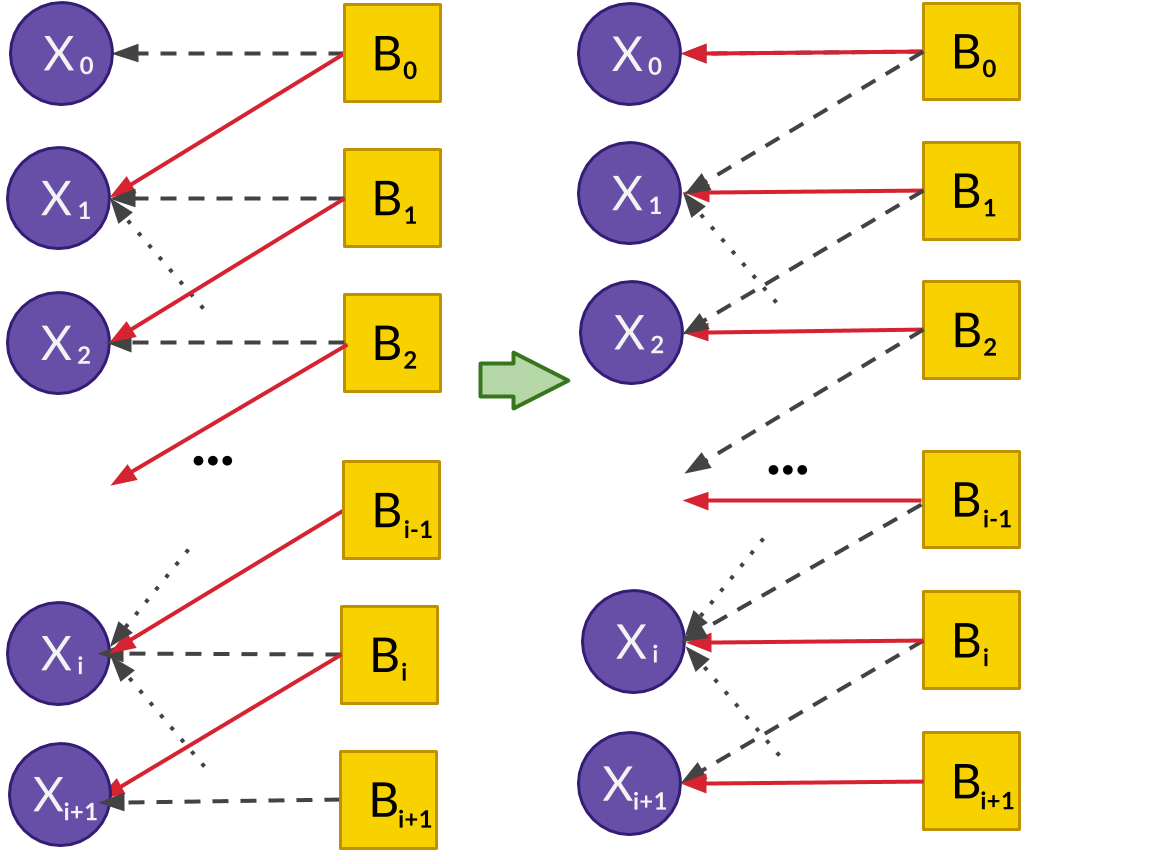

Proof. Suppose we have the optimum matching M which does not include a node $X_0$ on the LHS. Let $X_0$ be incident to box $B_0$. If $B_0$ is not matched with any node in matching $ M $, then we can add the edge $X_0 \rightarrow B_0$ to $M$, increasing its cardinality (contradiction!).

Hence, $B_0$ must be matched with a number, say $X_1$. Since $X_1$ has degree at least $2$, it should be incident to another box $B_1 (\neq B_0)$. In turn, $B_1$ would be matched with a number on the LHS. If not, we can augment to add edges $(X_0 \rightarrow B_0)$ and $(X_1 \rightarrow B_1)$ and remove $(X_1 \rightarrow B_0)$, increasing size of $M$ (contradiction!).

We continue building our path in the same way: $X_0 \rightarrow B_0 \rightarrow X_1 \rightarrow B_1 \rightarrow X_2 \rightarrow B_2 \cdots$. At step $i$ we will find a number $X_i$ because box $B_{i - 1}$ will have a matching edge $(B_{i - 1} \rightarrow X_i)$, or otherwise we can increase the size of the matching by alternating the matched edges. This number $X_i$ won’t be the same as $X_0 \cdots X_{i - 1}$ because the earlier $X_j$’s were found by matching with other $B_j$’s, or it was $X_0$ which is unmatched. Next, $X_i$ should have another unmatched edge to $B_i$ ($\textit{deg}(X_i) \geq 2$). This $B_i$ won’t be the same as previous $B_j$’s because previous $B_j$’s had exactly two edges and all these edges were included in the path.

Since we cannot continue building a path forever in a finite graph, the only conclusion is that $M$ is not a maximum matching. Hence, any maximum matching must include $X_0$. This concludes the proof. ∎

Putting it all together

We can now come up with an efficient algorithm to find the maximum stack. After constructing the graph, we proceed as follows:

- As long as numbers have degree 1, we can include them in the solution and delete its corresponding box (along with the box’s edge to the other number.)

- When there are no numbers with degree 1, we can include all numbers in our solution.

The complexity of this solution is $\mathcal{O}(N \log N)$.

from collections import Counter, defaultdict, deque

def stack(boxes):

# create bipartite graph from nums to boxes

degree = Counter()

num_to_box = defaultdict(list)

for bi, box in enumerate(boxes):

for dim in box:

degree[dim] += 1

num_to_box[dim].append(bi)

stack_size = 0 # count of the stack we build

deleted_boxes = set() # keep track of the boxes we include in the stack

# leaves are the nums adjacent to a single box

leaves = deque([x for x, d in degree.items() if d == 1])

# keep including nums from 'leaves' in our stack

while leaves:

leaf = leaves.pop()

# it's possible the leaf's box was deleted

if degree[leaf] <= 0:

continue

stack_size += 1 # yep, we can include it in the stack!

# delete the leaf's supporting box since it was included

for bi in num_to_box[leaf]:

if bi in deleted_boxes: # this box was already deleted

continue;

deleted_boxes.add(bi)

for dim in boxes[bi]:

degree[dim] -= 1

if degree[dim] == 1: # we might have created a new leaf

leaves.append(dim)

# all remaining numbers can be included since degree of each number is >= 2

# and boxes all have degree 2, and we can get a matching saturating the LHS

stack_size += sum([1 for x, d in degree.items() if d > 0])

return stack_size